The Great Rift

The Wadi Arabah is part of the Great Rift System (sometimes known as the Syrian-East African Rift). This runs from the coast of the Indian Ocean in Mozambique, to the Mediterranean coast of Turkey, where it meets the Eurasian Plate. The Earth’s outermost rigid, rocky layer, called the lithosphere, is broken, like a slightly cracked eggshell, into about a dozen separate rigid blocks, or plates.

Essentially, the Great Rift separates the Arabian Plate from the African Plate. Altogether the Great Rift System is about 6,400 km. long (c. 4000 miles), and averages 48-64 km. wide (c. 30-40 miles).

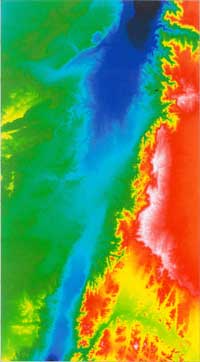

Geology of the Great Rift Valley (click for more detail)

About thirty million years ago Arabia started to move northwards in relation to Africa and Palestine. This was a result of the heating of the lithosphere and to its thermal expansion. This movement has been accompanied by extensive faulting, shattering, uplifting and sinking of the rocks of the earth’s crust along its boundary, and this led to the formation of the rift valley. The two highest mountains in Africa, Mounts Kilimanjaro and Kenya, were formed as a direct result of this movement. The rift is still considered to be active, and the movement to date is about 107 km.

The Wadi Arabah

The Wadi Arabah itself extends from the south end of the Dead Sea for 163 km. (110 miles) to the Gulf of Aqaba. It varies in width from 5 km. in the south section near Eilat, to 32 km. in the central sections. It rises in altitude going south from about 396 m. below sea level at the Dead Sea, to 230 m. below sea level in the southern Ghors, only a few kilometres to the south, and then rises to 200 m. above sea level near Gharandal, and eventually sea level at Eilat/Aqaba. On the east, the mountains of the

Jordanian plateau rise to c. 1500 m. above sea level (maximum 1727 m. near Tayba), and on the west are the dissected mountains and hills of the Negev desert, between 600 and 700 m. above sea level.

Contour map of the Wadi Arabah (click for more detail)

Once the valley was formed, the natural processes of erosion started to fill it with alluvial and wind-borne deposits. The floor of the Wadi Arabah is therefore covered with deep deposits of alluvium – gravels, sands and silts. The fine portions of these are continually blown about by the winds, forming sand dunes in certain areas, for example near Gharandal.

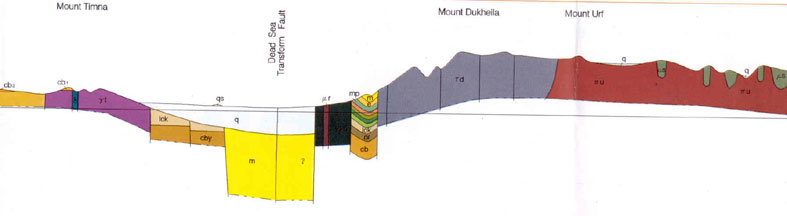

Section through the southern Wadi Arabah (courtesy of the Geological Survey of Israel)

Earthquakes

There is no record of major earthquakes in modern times, although several earthquakes are known from historical sources to have occurred in the vicinity of the southern Dead Sea, Karak, and the Wadi Arabah, including the earthquakes of AD 31, 363, 659/60, 1068, 1212, 1293, and 1456-59. The Wadi Arabah Earthquake Project, directed by Dr Tina Niemi of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, is attempting to document the earthquake history of the Wadi Arabah using archaeological excavation, geophysical surveys, and geologic subsurface probes.

Tectonic elements in the Dead Sea Rift Valley (click for more detail)

Of course, the main resource of the Wadi Arabah throughout antiquity was copper, from the mines at Timna and Faynan, respectively on the west and east sides of the wadi. Today, these two copper sources are 107 km. apart. This is exactly the amount of movement of the Arabian Plate against the African Plate, and it is quite clear that originally Timna and Faynan were one single geological deposit of copper.

Timna has a large number of copper mines, mining camps and smelting sites which were used sporadically from the Chalcolithic to Late Islamic periods, although it is best known for its Egyptian mines of the Late Bronze Age, and an associated temple to the Egyptian goddess Hathor, the patron deity of mining. The Faynan area was already used in the Palaeolithic period, with copper production from the Chalcolithic period

until at least the thirteenth century AD. The most intense period of exploitation was the Iron Age. It has been estimated that the Iron Age copper-production centres in the Faynan area produced between 6,500 and 13,000 tons of copper, considerably more than in any other period.

Originally one geological deposit of copper, due to tectonic movement the Timna deposit and the Wadi Feinan copper sources are now 107 km apart (map taken from Segev et al 1992: The Geology of the Timna Valley with Emphasis on Copper and Manganese Mineralization. Geological Survey of Israel Report 14) .